- Home

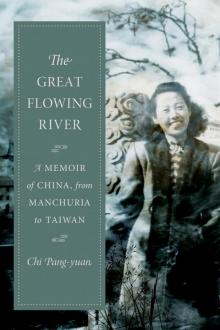

- Chi Pang-yuan

The Great Flowing River Page 3

The Great Flowing River Read online

Page 3

At the end of the Qing dynasty and the beginning of the Republican period, the three provinces of the northeast, which contained 1,230,000 square miles of grassland, were, in fact, in China’s domain. Owing to troubles within and without, the country grew weaker by the day, giving rise to border troubles over thousands of li shared with Russia and aggression on the part of the Japanese. The very resources and abundance of her land brought disaster down upon her, but throughout the ages, the indomitable spirits of the grassland had never been conquered.

I was born in a difficult age and spent my life wandering with no home to return to. All I had was a homeland in song. When I was young I heard my mother sing “Su Wu Herds Sheep” with a hidden bitterness. Twenty years later, having arrived in subtropical Taiwan from a land of ice and snow thousands of li away, in Taichung, which is a hundred li from the Tropic of Cancer, she actually sang while sitting next to my son’s cradle: “Su Wu herds sheep at the edge of Lake Baikal …” I said, “Mom, can’t you sing something else?” Sometimes she would sing “Lady Meng Jiang.” She said that at the age of nineteen she married into the Chi family, only to have her husband leave a month later to study, returning home a few times during the summer breaks, and when he did finally come home for good, he became involved in revolutionary work. Since then she had lived a wandering life and had never been able to return home. Looking after the young children, she felt like Su Wu, who looked at his lambs and was filled with hope that they would grow up and also bear lambs, waiting while sustaining almost impossible hope.

At thirty she finally crossed through Shanhaiguan on the three-day and two-night train trip that would reunite her family. From then on, as she followed her husband, her homeland grew ever more distant. Other than “Su Wu Herds Sheep,” she never sang a real lullaby.

Before I turned twenty, I had crossed the Liao River and gone to the Yangtze River, and had gone up the Min River to the Dadu River. In the eight years of the War of Resistance against Japan, my homeland continued to reside in song. During the war, people from all parts of China hastened to the wartime capital of Chongqing. Wandering homeless on muddy roads, amid falling bombs, everyone sang, “The Great Wall, the Great Wall, our home lies beyond the Great Wall.” But what was that home like? When we sang “My home is on the Songhua River in the northeast,” everyone thought of their own home, on the Yongding River, the Yellow River, the Han River, the Huai River, the Gan River, the Xiang River, the Gui River, the Yi River, or any of the other beautiful rivers of China: “Every night the rivers sob as they flow by, all as if flowing through my heart.”

THE BEGINNING OF MY LIFE

I was born on the day of the Lantern Festival in 1924 in my home province of Liaoning. At that time of the year, the temperature is often minus five to twenty-five degrees, or even as low as minus forty. My mother was ill during her pregnancy, so I was born weak. One day when I was about a year old, I developed a high fever that would not abate and my breath grew so faint that it seemed suddenly on the verge of stopping altogether. Sitting on the kang, a brick bed heated by the kitchen fire and used in northeast China, my mother held me close to her and refused to let go. A relative who had come to the house to celebrate the festival said, “The child is dead; there’s barely any breath left in her. Why do you cling to her so? Let her go.” My mother kept crying but refused to release me. By then it was already midnight and my grandmother said, “Okay, have one of the hired hands ride to town and find a doctor who can ride a horse, and see if he can come and save the girl’s life.” The hired hand went to town, which was about ten li from where we lived, and actually found a doctor who could ride a horse and was willing to brave the subzero temperatures in the middle of the night and come to our village. He came into our courtyard, and I was revived. The lifeless child my mother refused to part with became a child filled with vitality, which lasted all her life.

Statistics have it that the infant mortality rate was around 40 percent in those days. My life was like a small oil lamp in the wind, and the protection of my mother and that of my “guardian angels” was like a glass surrounding it, preventing it from being snuffed out.

Shortly thereafter, the doctor returned to our village to treat a patient. Carrying me in her arms, my mother went to see him and said, “You saved this child’s life. Her father is studying in Germany and hasn’t yet named her. Please do give her a name to mark your predestined affinity!” The doctor chose the name Pang-yuan and thus bestowed a double blessing on me at the beginning of my life.

Growing up, I learned that my name was derived from a line in the poem “She Who Is to Grow Old with the Lord” from the Book of Songs: “Oh, bright are your eyes, well-rounded your forehead! Truly a person like that, she is the beauty of the country.” A few years ago, a reader sent me a photocopy of a page from an essay in Fan Chengda’s Clear Lake Collection, from the Song dynasty, that contains this line: “Chi Pang-yuan, a woman of virtue.…” I actually possess the same name and surname as a virtuous woman who lived several centuries ago, something both an honor and a bit terrifying. In this new world of ours, in which I have spent half my life struggling between family and career, I often think of that doctor in the mountain village of my old home. I hope he knows how hard I have worked to be worthy of his blessing in an age when a girl’s life was considered a mere trifle.

THE CHI FAMILY OF TIELING

My childhood was a world without a father. At the age of two, I caught a fleeting glimpse of my father returning home at night during a snowstorm, and then fleeing once again early the next morning. Two days later, my grandmother and my mother took my older brother and me to a nearby village, even smaller than ours, to hide there at the home of a relative for several days. We fled because the troops of Zhang Zuolin were trying to capture Chi Shiying, who had participated in Guo Songling’s mutiny. They wanted to apprehend and execute his entire family. While we were there, I cried and shouted every day when it got dark, “I want to go home! I want to go home!” This compounded the difficulty, and fearing lest others be dragged in, everyone decided that we should go home and accept our fate.

The Chi family of Tieling arrived in Fengtian (Shenyang) from Xugou County (now incorporated into Taiyuan City), Shanxi Province, in the eighteenth century, first serving as civil officials there and then settling down. By my father’s generation the family had been there for eight generations. The family estate was situated on Little Western Hill west of Fanjiatun, about five li from the Luanshi Mountain Train Station on the Chinese Eastern Railway. The family property consisted of about four thousand mu (1 mu = 733 1/2 square yards) of farmland, which made us an average large-scale landowner.

My grandfather Chi Pengda had four brothers. As a young man, he had no desire to stay in the countryside and farm the family land, so he left to study at a military academy and graduated from the former Baoding Army Accelerated School. Later, he began as a battalion commander in Zhang Zuolin’s Fengtian Army, then rose from regimental commander to brigade commander. He served Zhang Zuolin loyally for more than twenty years. My father was his only son, and after studying abroad in Germany, he returned home with his head full of new thought and of saving the country and the people, so he took part in Guo Songling’s revolutionary activities against Zhang Zuolin. It was only one month from when Guo’s troops were deployed from Tianjin to when they were defeated outside Shanhaiguan. At that time, my grandfather was garrisoned at Baoding in Hebei Province, unaware of what had happened. Everyone in the Fengtian Army thought Marshal Zhang was certain to have my grandfather executed, but to everyone’s surprise, he told his subordinates, “The father is of one generation, the son another, and I’m not interested in settling any score on that account. Chi Pengda has been with me many years and is loyal. His son is a scoundrel who went overseas to study and came back muddleheaded, but that doesn’t mean I should kill his father.” Later, my grandfather suffered minor wounds during a skirmish, caught a chill, and died. He was only fifty years old when he passed aw

ay. Zhang Zuolin was of humble origin, but he had the gallantry and the spirit of righteousness of the rough-and-ready woodland heroes of his time, and refused to appease the Japanese. He was killed in an ambush when they blew up his train at Huanggutun, and so ended the legendary age of the warlord, leaving the northeast in a perilous situation. His son, Zhang Xueliang, assumed his title, power, and wealth, but lacked his intelligence or sense of honor. Northeast China’s hopes for soverign prosperity were never to be realized.

My grandmother Zhang Congzhou was Manchu. She married into the Chi family from a neighboring village at the age of eighteen and bore a son and two daughters. In the early days of my grandfather’s military career, she accompanied him to wherever he was garrisoned, but later, because someone had to look after the family property, she came back to settle down, all alone taking care of the big estate she called home. She and my mother, two lonely women who kept watch all year long, along with three young children and twenty hired hands, passed their days with the spring plantings and the autumn harvests. I ran all over the mountains with my older brother, picking self-heal on Little Western Hill and cucumbers and blackberries in the back garden. In winter we would play on the frozen stream, impressions still vivid today. My grandmother was a dignified, generous, gentle, and benevolent person, who had much sympathy for and took pity on my mother, her daughter-in-law, who had married her only son. But in that age, she too had become a mother-in-law through enduring life as a daughter-in-law, and thus knew which rules were unalterable; so although she treated her daughter-in-law well and would never go out of her way to cause her trouble, and always spoke to her in a tender voice, rules were still rules. Even though there were a number of hired hands and servants in the house, when a husband’s mother sat down to eat, the daughter-in-law would stand attentively to one side, her hands at her sides. That’s how things were done in a family of position. My grandmother had a most tender regard for me, and it was she who had actually saved my life. Later when I went to the Western Hills Sanatorium in Beiping, she was reduced to tears, the memory of which makes me feel guilty to this day.

It was a big event whenever Grandfather came home. He was a powerful official in those days and had four guards standing at the door. Dress codes and table manners were of particular concern, and if something was not up to his standard, he’d throw a fit. No one in the family could breathe easy until he returned to the garrison. My father said that Grandfather was quite open to the new thinking, but was a person of such authority that no one dared argue with him. Shortly after I was born, my grandfather came home from the garrison and took a glance at the infant wrapped in a quilt on the kang. With an imposing manner, he took a seat in the main hall and said, “Grab that little kitten and bring her here so that I can have a look!” For some unknown reason, the little baby who didn’t even weigh five pounds and wasn’t worth being “carried” had aroused fierce protective instincts in him. He ordered, “No one shall bully this granddaughter of mine!” (This meant especially my older brother, that sturdy grandson of his.) Although it was an age when men were valued over women, the Chi family was small and all children were treasured. That military order only enhanced my position at home.

While in the military, my grandfather received a gift for his fortieth birthday: a delicate and graceful twenty-year-old concubine. Whenever he was garrisoned someplace new or went to war, he’d send her home. It wasn’t long before she developed tuberculosis and died. My grandmother treated her well and raised her newborn son (who was named Chi Shihao). I was the same age as this little uncle, so we often played together and were teased by my older brother and cousins. My little uncle grew up under the blessed protection of my grandmother. After north China fell to Japan, he graduated from high school and was conscripted, and one day, while walking down a village lane dressed in a Japanese military uniform, he was shot in the back by the anti-Japanese underground.

Grandmother was sad and lonely her entire life. Her only son left home at thirteen to study in Shenyang, then went to Tianjin, then Japan, and then Germany, and only came home during summer breaks. After returning from studying abroad, he joined the revolution and thereafter lived a life on the run to the far corners of the earth, to be parted from her until she died. After the Mukden Incident in 1931, she took two of my aunts and my little uncle to live in Beiping. Later, in her middle age, she was often ill and confined to bed. My two aunts were well after they got married. The older, Chi Jinghuan, who was called Fourth Aunt according to the ranking of the entire family and accompanied her husband, Shi Zhihong, to study in Japan, was intelligent and brave. After 1933, my father returned to the north to organize and lead the underground resistance against the Japanese. During that time until just before the Japanese were defeated, she went to the Beiping train station and other locations many times to help members of the underground get in and out of Shanhaiguan. Every time she met or saw off someone from the resistance, she would say they were a cousin. Once the people at the railway station got to know her better they asked her, “How come you have so many cousins?” In all likelihood, they probably knew what was going on, but since everyone hated the Japanese, no one revealed what she was up to. Moreover, she was usually carrying a small child, and surreptitiously gave out gifts on New Year’s Day and other festivals. Later, in Taiwan, many of these “cousins” remembered my aunt with gratitude and admiration. My two aunts’ husbands couldn’t remain in Japanese-controlled territory after the start of the war because of their anti-Japanese activities and so accompanied my family to the rear. Later they both fell ill and died in Chongqing, while my two aunts stayed behind with their seven children in Beiping, where they lived with my grandmother and performed their filial duty. My grandmother died of cancer. She was only sixty-four, in the first year of the War of Resistance. We fled to Hankou twenty days before Nanjing fell into Japanese hands, and after catching our breath a little, we were off to Xiangxiang in Hunan, where we stayed for half a year. From there we trudged thousands of li over the Hunan–Guizhou Road, overcoming great difficulties to arrive in Sichuan. Only after we made it to Chongqing did we hear about Grandmother’s passing the year before, and for this my father felt great remorse his entire life.

THE CRYING IN THE FORAGE GRASS

My maternal grandfather, Pei Xincheng, was Han Chinese; my maternal grandmother was Mongol. They lived in Xintaizi, a small village twenty li from our home. My grandfather was a wealthy gentleman who owned a mill and lots of land. In 1904, he accompanied a prefectural educational inspector by the name of Jiang to inspect Fanjiatun Primary School. He was deeply impressed by the Chi boys from Little Western Hill Village, Chi Shichang (my father’s second cousin) and Chi Shiying. The two of them were determined to advance in school and serve their country when they grew up. That day they were studying civics, and my grandfather and Mr. Jiang heard small, thin Chi Shiying ask his teacher why the Japanese and Russians were fighting in our homeland. When he was young and in a tutorial school, he saw the artillery action on Southern Mountaintop in which the Russians were routed and the Japanese victorious. Before the fighting ceased, the Japanese bivouacked at our estate for one or two months, until my grandfather sent the men back home. Several years later, the Pei family and the Jiang family requested a respected local person to propose marriage. Educational Inspector Jiang Xianxue’s daughter and my second uncle were the same age, while Miss Yuzhen of the Pei family was the same age as my father. The boys were handsome and the girls beautiful and their family backgrounds were well matched, so the heads of the families agreed and made the engagements. At that time, my father and my second uncle were in high school in Shenyang, so they had no opportunity to express their opinion. During the summer break, my father accompanied the family elders to the village of Xintaizi ostensibly to see the grapevines planted by the Pei family, something rare in northeast China. It was then that he saw my mother, who was only fourteen. She was favorably impressed by her fiancé, whom she saw only once, and thought he would ma

ke a far better husband than someone from the country. She probably had fond dreams and saw only the good side of things and from then on imagined the outside world with longing.

My second uncle had a huge influence on my father from an early age. He was four years older than my father and filled with new ideas. When news of the Revolution of 1911 reached Shenyang, he cut off his queue, and his envious nine-year-old brother followed suit. He went with his brother to the governor general’s office, where they knelt for several hours as part of an effort to petition for the establishment of a parliament. Dissatisfied with the curriculum in junior high school, the two brothers went to Tianjin without permission, where they took and passed the entrance exam for Xinxue College, run by English missionaries; from there they went to study in Japan. My father, owing to his brilliant test scores, was awarded official funding and entered Tokyo First High School, from where he was assigned to Kanazawa Fourth High School the following year. During the summer of the year he turned nineteen, he was called home to marry, because Grandmother was sick and someone was needed to run the household. My father refused to return, so my grandfather dispatched an uncle to Japan for the sole purpose of bringing him home. My father always told us that he had several conditions to be met if he were to be married: no kowtowing, no red clothing, no face covered with red cloth, riding a horse instead of being carried in a palanquin; moreover, he wanted to take his wife abroad to study with him. If these conditions were met, he’d go home; if not, he would not return; the family agreed. After his return, however, everything was done according to tradition save his riding a horse. One month later, he returned to Japan.

The Great Flowing River

The Great Flowing River